As a financial journalist, I spend a lot of time seeing what people well smarter than me have to say about money, markets, and the economy. One report, written by the Federal Reserve’s own economists, left me with not exactly an upbeat outlook.

1. Researchers at the US central bank just published a paper warning that a historic surge in the percentage of distressed American companies could worsen the fallout from the Fed’s inflation battle. Plainly, they said high borrowing costs could cause a huge number of companies to crumble.

“The share of nonfinancial firms in financial distress has reached a level that is higher than during most previous tightening episodes since the 1970s,” Ander Perez-Orive and Yannick Timmer wrote.

The Fed’s 10 consecutive interest rates — intended to quell historically high prices — threaten to hammer business investment, employment, and economic activity. Now, the economists said, it’s possible that debt-ridden companies will avoid spending money on new developments or facilities, hiring, or production.

The full extent of the damage remains to be seen, but as of now, the central bank authors said about 37% of firms are in trouble.

That is, more than a third of companies could default in the coming months, thanks to tightening monetary policy. Pardon the jargon, but here’s how the researchers put it:

“Our hypothesis is that following a policy tightening, access to external financing deteriorates more for firms that are in distress than for healthy firms, while following a policy easing, external financing conditions do not change appreciably enough for the two groups of firms to trigger a differential response.”

Got it? It’s okay, I didn’t either the first time around.

Basically, they are predicting that companies feel pain in times of policy tightening, especially those with weaker balance sheets to begin with. But at the same time, loosening of policy doesn’t necessarily translate to smoother sailing in the same way.

Courtesy of Phil Rose, Business Insider

Click here for the full article link

The Federal Reserve promotes the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions and monitors their impact on the financial system. It is responsible for supervising—monitoring, inspecting, and examining—certain financial institutions to ensure that they comply with rules and regulations, and that they operate in a safe-and-sound manner. The Federal Reserve supervises bank holding companies, savings and loan holding companies, the U.S. operations of foreign banking organizations, and state member banks of varying size and complexity.

The Federal Reserve promotes the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions and monitors their impact on the financial system. It is responsible for supervising—monitoring, inspecting, and examining—certain financial institutions to ensure that they comply with rules and regulations, and that they operate in a safe-and-sound manner. The Federal Reserve supervises bank holding companies, savings and loan holding companies, the U.S. operations of foreign banking organizations, and state member banks of varying size and complexity.

The Federal Reserve Board publishes its semiannual Supervision and Regulation Report to inform the public and provide transparency about its supervisory and regulatory policies and actions as well as current banking conditions. Previous reports are available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/supervision-and-regulation-report.htm.

For more information on how the Federal Reserve Board promotes the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions and the financial system see https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg.htm.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-MA, on Tuesday proposed a legislative route to do the same, but Republicans and even some Democrats are waiting on the Fed’s review of recent bank failures.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-MA, on Tuesday proposed a legislative route to do the same, but Republicans and even some Democrats are waiting on the Fed’s review of recent bank failures.

The Federal Reserve is reviewing the capital and liquidity requirements it imposes on banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times reported Tuesday, citing a person familiar with the matter.

Such an adjustment would have put Silicon Valley Bank, which counted $209 billion in assets before it failed Friday, and Signature Bank, which had $110 billion, under potentially stricter guidelines.

The Fed in October proposed requiring banks with between $250 billion and $700 billion in assets to carry long-term debt that would be converted into equity to recapitalize the bank in times of extreme stress. That would put the burden of losses on investors rather than taxpayers in a bailout situation.

Additionally, Michael Barr, the Fed’s vice chair for supervision, warned in December that the central bank would complete a “holistic” review of the framework behind stress tests that set capital requirements, but he didn’t give a time frame then.

Last week’s bank failures may well hasten that timeline.

Proposed changes may require more banks to report unrealized gains and losses on some securities as part of their capital, according to The Wall Street Journal. Silicon Valley Bank, for example, concentrated its balance sheet in long-term assets, leaving it more susceptible to failure if customers withdrew their funds immediately.

The rule-change process for the Fed’s October proposal on $250 billion-to-$700 billion-asset banks allows for public comment and takes months. The central bank, however, can choose, under Title 12 of the U.S. Code, to issue an order placing new requirements such as resolution plans, counterparty credit limits or annual stress tests, on banks with more than $100 billion in assets to protect financial stability, American Banker reported.

“That’s something that the Fed could do tomorrow,” Peter Conti-Brown, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, told the publication.

Some lawmakers are blaming event bank failures, in part, on a 2018 rollback of parts of the Dodd-Frank Act.

S. 2155, sponsored by Sen. Mike Crapo, R-ID, raised — from $50 billion in assets to $200 billion — the threshold of banks subject to the Fed’s toughest supervisory measures, including stress tests and capital and liquidity requirements.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-MA, on Tuesday proposed a bill to repeal S. 2155.

Courtesy of Dan Ennis, BankingDive

Lael Brainard submitted her resignation February 14, 2023 as Vice Chair and a member of the Federal Reserve Board, effective on or around February 20, 2023. She has been a member of the Board since June 16, 2014, and Vice Chair of the Board since May 23, 2022.

Lael Brainard submitted her resignation February 14, 2023 as Vice Chair and a member of the Federal Reserve Board, effective on or around February 20, 2023. She has been a member of the Board since June 16, 2014, and Vice Chair of the Board since May 23, 2022.

“Lael has brought formidable talent and superb results to everything she has done at the Federal Reserve,” Chair Jerome H. Powell said. “That lengthy list includes her thought leadership on monetary policy and economic research, her stewardship of financial stability and the payments system, strengthening the financial system both domestically and globally, and helping to manage the immense operational agency challenges during the pandemic. My colleagues and I will truly miss her.”

Dr. Brainard was nominated to the Board by President Obama and then re-nominated as Vice Chair by President Biden. During her time at the Board, she chaired multiple committees, including the Committee on Financial Stability, the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, the Committee on Payments, Clearing, and Settlement, and the Committee on Board Affairs, among others. She also served as chair of the Federal Open Market Committee’s communication subcommittee.

Dr. Brainard played a vital role during the response to the pandemic and has provided wise counsel on monetary policy, as well as contributing to the creation of the Fed Listens initiative. The Board published its first financial stability report under her leadership. She has led the interagency process to strengthen the Community Reinvestment Act, as well as the Board’s work to establish the FedNow real-time payments network.

Dr. Brainard has represented the Board internationally, including at the Bank for International Settlements, the Group of Seven, and the Financial Stability Board. While at the Fed, Dr. Brainard was chair of the Financial Stability Board’s Standing Committee on Assessment of Vulnerabilities and also chair of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Working Party 3 committee. She will soon start as director of the National Economic Council, which advises the president on domestic and global economic policy.

Before her time at the Fed, she served as Under Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury and counselor to the Secretary of the Treasury, where she received the Alexander Hamilton Award. Prior to that, Dr. Brainard was vice president and the founding director of the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution. Before that, she served as the Deputy National Economic Adviser and Deputy Assistant to the President and G-7 Sherpa. From 1990 to 1996, Dr. Brainard was assistant and associate professor of applied economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management.

Dr. Brainard received a B.A. with university honors from Wesleyan University and an M.S. and a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University, where she was awarded a National Science Foundation Fellowship. She is also the recipient of the Harvard Centennial Medal and the White House Fellowship.

Click here to see the release.

The Federal Reserve Board on Thursday released the hypothetical scenarios for its annual stress test, which helps ensure that large banks are able to lend to households and businesses even in a severe recession. This year, 23 banks will be tested against a severe global recession with heightened stress in both commercial and residential real estate markets, as well as in corporate debt markets.

2023 Stress Test Scenarios (PDF)

The Board’s stress test evaluates the resilience of large banks by estimating losses, net revenue, and capital levels—which provide a cushion against losses—under hypothetical recession scenarios that extend two years into the future. The scenarios are not forecasts and should not be interpreted as predictions of future economic conditions.

In the 2023 stress test scenario, the U.S. unemployment rate rises nearly 6-1/2 percentage points, to a peak of 10 percent. The increase in the unemployment rate is accompanied by severe market volatility, a significant widening of corporate bond spreads, and a collapse in asset prices.

In addition to the hypothetical scenario, banks with large trading operations will be tested against a global market shock component that primarily stresses their trading positions. The global market shock component is a set of hypothetical shocks to a large set of risk factors reflecting market distress and heightened uncertainty.

For the first time, this year’s stress test will feature an additional exploratory market shock to the trading books of the largest and most complex banks, with firm-specific results released. This exploratory market shock will not contribute to the capital requirements set by this year’s stress test and will be used to expand the Board’s understanding of the largest banks’ resilience by considering more than a single hypothetical stress event. The Board also will use the results of the exploratory market shock to assess the potential of multiple scenarios to capture a wider array of risks in future stress test exercises.

Click here to read the entire release.

Governor Bowman presented identical remarks to the Florida Bankers Association Leadership Luncheon Events, Tampa, Florida, on January 11, 2023.

Governor Bowman presented identical remarks to the Florida Bankers Association Leadership Luncheon Events, Tampa, Florida, on January 11, 2023.

Thank you, Bill, and I’d also like to thank Alex Sanchez and the Florida Bankers Association for the invitation to be with you today. It is a pleasure to be here in person to discuss issues that are top of mind for all of us as we begin the new year. I will start with some thoughts about the Federal Reserve’s ongoing effort to lower inflation, which continues to be much too high. I will then touch on other issues in the Fed’s purview, including bank supervision and regulation.1

While the Fed has access to a staff of expert economists and a seemingly infinite flow of economic data to inform our decision-making, I often find that the most valuable data comes directly from the experiences and perspectives of those who are engaged in and supporting the economy through the financial system. In my more than four years as a member of the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), I have learned that there are few who understand the economy more directly than bankers, business owners and the customers you serve.

Monetary Policy

Let me begin by discussing the Fed’s efforts to lower inflation. Inflation is much too high, and I am focused on bringing it down toward our 2 percent goal. Inflation affects everyone, but it is especially harmful to lower- and middle-income Americans, who spend a greater share of their income on necessities like food and housing. Stable prices are the bedrock of a healthy economy and are necessary to support a labor market that works for all Americans.

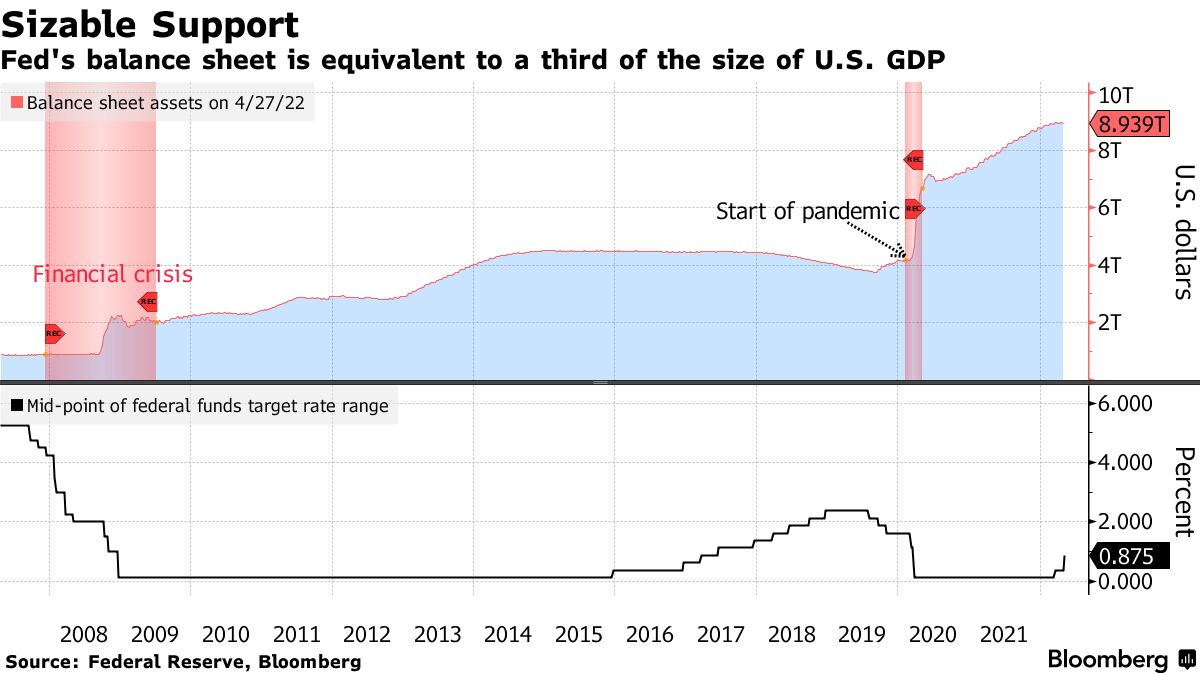

Over the past year, I have supported the FOMC’s policy actions to address high inflation, and I am committed to taking further actions to bring inflation back down to our goal. Since last March, the FOMC has been tightening monetary policy through a combination of increasing the federal funds rate by 4-1/4 percentage points and reducing our balance sheet holdings.

In recent months, we’ve seen a decline in some measures of inflation but we have a lot more work to do, so I expect the FOMC will continue raising interest rates to tighten monetary policy, as we stated after our December meeting.2 My views on the appropriate size of future rate increases and on the ultimate level of the federal funds rate will continue to be guided by the incoming data and its implications for the outlook for inflation and economic activity.

I will be looking for compelling signs that inflation has peaked and for more consistent indications that inflation is on a downward path, in determining both the appropriate size of future rate increases and the level at which the federal funds rate is sufficiently restrictive. I expect that once we achieve a sufficiently restrictive federal funds rate, it will need to remain at that level for some time in order to restore price stability, which will in turn help to create conditions that support a sustainably strong labor market. Maintaining a steadfast commitment to restoring price stability is essential to support a sustainably strong labor market.

To this point, unemployment has remained low as we have tightened monetary policy and made progress in lowering inflation. I take this as a hopeful sign that we can succeed in lowering inflation without a significant economic downturn. It is likely that as a part of this process, labor markets will soften somewhat before we bring inflation back to our 2 percent goal. While the effects of monetary policy tightening on the job market have generally been limited so far, slowing the economy will likely mean that job creation also slows. And if there are unforeseen shocks to the economy, growth may slow further. It’s important to keep in mind that there are costs and risks to tightening policy to lower inflation, but I see the costs and risks of allowing inflation to persist as far greater. These dynamics make the difficult decisions facing the FOMC even more challenging, but it is absolutely necessary that the Committee achieves our goal of price stability.

From the late 1960s through the mid-1980s, the U.S. economy experienced high inflation, high unemployment, and declining living standards. During that time, policymakers prematurely eased monetary policy when the economy weakened, and inflation remained high. The FOMC was forced to return to tightening monetary policy, causing a deep recession in 1981 and 1982. This is an important lesson that guides my thinking about monetary policy and my continued support for policy actions that will continue to lower inflation.

It is also important to remember that today’s inflation is a global concern. This is because some of the factors driving inflation in the United States are global, including the disruption to goods production and trade during the pandemic, the shutdown and reopening of large economies, and the more recent disruption of food and energy supplies due to conflicts abroad. Monetary policy can do very little to improve supply disruptions, but it can help bring supply and demand into better alignment.

While the path ahead looks uncertain, I am encouraged by three specific developments. The first is the ongoing strength of the labor market, which was further supported with last Friday’s jobs report. So far, the job market has remained resilient despite higher interest rates and slower growth. The second development is that the balance sheets of households have remained strong, with low debt levels. Low debt and strong balance sheets together with the strong labor market mean that consumers and businesses can continue to spend even as economic growth slows. The third point is the strength of the U.S. banking system, with high levels of capital and liquidity, due in large part to the reforms adopted after the last financial crisis.

I will turn now to the banking and payments issues on the Fed’s agenda, which include crypto and digital assets, innovation in payments, climate change and banking supervision, and likely changes to the rules implementing the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA).

Cryptocurrency

The dysfunction in cryptocurrency markets has been well-documented, with some crypto firms misrepresenting that they have deposit insurance, the collapse of certain stablecoins, and, most recently, the bankruptcy of the FTX cryptocurrency exchange. These events have made it clear that cryptocurrency activities can pose significant risks to consumers, businesses, and potentially the larger financial system.

While the traditional financial system has limited exposure to cryptocurrencies, I expect that some banks will continue to explore how to engage in crypto-related activities. The Fed and other banking agencies will continue to focus in this area, in light of the significant risks these activities may pose. But the bottom line is that we do not want to hinder innovation. As regulators, we should support innovation and recognize that the banking industry must evolve to meet consumer demand. By inhibiting innovation, we could be pushing growth in this space into the non-bank sector, leading to much less transparency and potential financial stability risk. We are thinking through some of these issues and what a regulatory approach could look like.

Payments

The Fed plays an important role in fostering the safety and efficiency of the U.S. payments, clearing, and settlement systems. There have been a number of interesting developments on payments that continue to be top of mind for policymakers. One of these is the push for real-time payments. Since 2019, the Fed has been working to launch FedNow, a new faster payments system that will be available in the first half of 2023. FedNow will help transform the way payments are made through new direct services that enable consumers and businesses to make payments conveniently, in real time, on any day, and with immediate availability of funds for receivers. FedNow will enable depository institutions of every size, and in every community across America, to provide safe and efficient instant payment services.

We have also been studying the concept of a central bank digital currency (CBDC). Several foreign governments and central banks are exploring digital currency, and there are many competing proposals suggesting a need to create a digital currency. The common theme underlying the need in these proposals is the desire to increase the speed and reduce the cost of financial transactions. Last January, the Fed published a paper soliciting comment on possible forms and uses of a CBDC in the United States. The Fed continues to study the idea, although much of what supporters hope to achieve with a central bank digital currency may be provided through FedNow and existing private payment services. In any case, initiatives to make payments faster and more efficient will continue to be an area of focus.

Climate Supervision

Climate has also been a recent focus for Fed supervision, but our narrow interest in this area it is limited to the largest banks. Last fall, the Fed announced an exploratory pilot study with six of the GSIBs that is narrowly focused on the goal of enhancing the ability of supervisors and firms to measure and manage climate-related financial risks, not credit allocation. The Fed has also published a climate guidance proposal for banks over $100 billion in assets. These climate efforts do not apply to smaller and community banks. Smaller and community banks already integrate and comply with robust risk management expectations. The Fed views its role on climate as a narrow focus on supervisory responsibilities and limited to our role in promoting a safe, sound and stable financial system. While this climate supervision effort is a new area of focus, it has been a longstanding supervisory requirement that banks manage their risks related to extreme weather events and other natural disasters that could disrupt operations or impact business lines.

Community Reinvestment Act

The last item on our regulatory agenda that I will note in my remarks today is the proposal to update the Community Reinvestment Act. The CRA requires the Fed and other banking agencies to encourage banks to help meet the credit needs of their communities, including low- and moderate-income communities. This rule was last updated 25 years ago, and the banking industry has changed dramatically since the 1990s. The proposal reflects these industry changes, including recognizing internet and mobile banking services, it also attempts to provide clarity and consistency, and it could enhance access to credit for these low- and moderate-income communities. I am fully supportive of these efforts, but I also share the concern noted in public comments that have suggested that some of the elements included in this overhaul of the CRA framework result in significant new regulatory burden, particularly for the smallest and community banks. As we continue this important rulemaking process, it will be critical for the Fed to carefully weigh the costs and benefits of any changes before finalizing a proposal.

I will stop there so we can move on to our conversation. Thank you again, for the opportunity to be with you today. I look forward to the discussion.

1. These views are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my colleagues on the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Open Market Committee. Return to text

2. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2022), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement,” press release, December 14. Return to text

Governor Christopher J. Waller, at “Digital Currencies and National Security Tradeoffs,” a symposium presented by the Harvard National Security Journal, Cambridge, Massachusetts

October 14, 2022 — As the payment system continues to evolve rapidly and the volume of digital assets continues to grow, it is critical to ensure that we keep both the benefits and risks of digital assets in the policy conversation, including the implications for America’s role in the global economy and its place in the world. My speech today focuses on exactly this issue and on an aspect of the digital asset world that is now the center of domestic and international attention—central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and how they relate to the substantial international role of the U.S. dollar.1

October 14, 2022 — As the payment system continues to evolve rapidly and the volume of digital assets continues to grow, it is critical to ensure that we keep both the benefits and risks of digital assets in the policy conversation, including the implications for America’s role in the global economy and its place in the world. My speech today focuses on exactly this issue and on an aspect of the digital asset world that is now the center of domestic and international attention—central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and how they relate to the substantial international role of the U.S. dollar.1

In January 2022, the Federal Reserve Board published a discussion paper on CBDCs to foster a broad and transparent public dialogue, including the potential benefits and risks of a U.S. CBDC.2 To date, no decisions have been made by the Board on whether to move forward with a CBDC. But my views are well known. As I have said before, I am highly skeptical of whether there is a compelling need for the Fed to create a digital currency.3

I am not a national security expert. But one area where economics, CBDCs, and national security dovetail is the role of the dollar. Advocates for creating a U.S. CBDC often assert how it is important to the long-term status of the dollar, particularly if other major jurisdictions adopt a CBDC. I disagree. As I will discuss, the underlying reasons for why the dollar is the dominant currency have little to do with technology, and I believe the introduction of a CBDC would not affect those underlying reasons. I offer this view, again, in the spirit of dialogue, knowing how important these issues are, and I am very happy to engage in vigorous debate regarding my view. I remain open to the arguments advanced by others in this space.

The Role of the U.S. Dollar

After World War II and the creation of the Bretton Woods system, the U.S. dollar served as the central currency for the international monetary system. Other countries agreed to keep the exchange value of their currencies fixed to the dollar, and eventually, countries came to settle international balances in dollars.4 That role has continued long after the Bretton Woods system dissolved.

By any measure, the dollar is the dominant global currency—for funding markets, foreign exchange transactions, and invoicing. It also is the world’s predominant reserve currency.5

In terms of the dollar’s reserve currency status, 60 percent of disclosed official foreign reserves are held in dollars, far surpassing the shares of other currencies, with the majority of these dollar reserves held in safe and liquid U.S. Treasury securities.6 Even in a world of largely floating exchange rates, many countries either implicitly or explicitly anchor their currencies to the dollar; together, these countries account for about half of world gross domestic product.7

The dollar is by far the dominant currency for international trade. Apart from intra-European trade, dollar invoicing is used in more than three-fourths of global trade, including 96 percent of trade in the Americas.8 Approximately 60 percent of international and foreign currency liabilities—international banking loans and deposits as well as international debt securities—are denominated in dollars. And the dollar remains the single most widely used currency in foreign exchange transactions. Why does this matter to the United States? As indicated in the Board’s CBDC discussion paper, the dollar’s international role lowers transaction and borrowing costs for U.S. households, businesses, and government. It widens the pool of creditors and investors for U.S. investments. It may insulate the U.S. economy from shocks from abroad.9 It also allows the United States to influence standards for the global monetary system.10

The dollar’s role doesn’t only benefit the United States. The dollar serves as a safe, stable, and dependable form of money around the world. It serves as a reliable common denominator for global trade and a dependable settlement instrument for cross-border payments. In the process, it reduces the cost of transferring capital and smooths the world of global payments, including for households and businesses outside of America.11For example, consider the dollar’s role in foreign exchange markets. To make a foreign exchange transaction between two lightly traded currencies, it is often less expensive to trade the first currency with the dollar, and then to trade the dollar with the second currency, rather than to trade the two currencies directly.

The factors driving the dollar’s role as a reserve currency are well researched and well demonstrated, including the depth and liquidity of U.S. financial markets, the size and openness of the U.S. economy, and international trust in U.S. institutions and the rule of law. We must keep these factors in mind in any debate regarding the long-term importance of the dollar.

CBDCs and the U.S. Dollar

Threats to the U.S. dollar’s international dominance are numerous, including shifting geopolitical alliances and pressure to invoice in alternative currencies, as well as deeper and more open foreign financial markets. My focus today is on just one supposed threat—namely, the purported shifting payments landscape as a result of the growth of digital assets, particularly CBDCs.

Recent years have seen a number of changes to the payments system, from instant interbank payments to mobile payment services to a shift toward nonbank payment providers. Some of this shift has been through the rise in digital assets and include cryptocurrencies and other crypto-assets such as stablecoins, which have money-like characteristics. They also include CBDCs. A CBDC is a digital instrument that is a liability of the central bank. That is all it is—a direct liability of a central bank.

What major security gap exists that a CBDC, and only a CBDC, can close? What would be the effect of CBDCs and other digital money-like instruments on the role of the dollar? There are many ways to approach this question, but I want to do so by using a simple example: What is it about a CBDC that would make a non-U.S. company, engaging in international financial transactions, more or less likely to use the dollar? This example, of course, focuses on the reasons for why contracts are generally invoiced in U.S. dollars, which is just one feature of the dollar’s international role. To me, however, it simplifies the overall question regarding the effect of a CBDC on the dollar’s dominance.

We can break down this question into three others: First, would a foreign CBDC affect this non-U.S. company’s decisions? Second, would a U.S. CBDC affect them? And, third, while stablecoins are not CBDCs, how would a privately issued stablecoin have a different effect?

Foreign CBDCs

First, I will consider the emergence of one or more foreign CBDCs in a world with no U.S. CBDC. What would be the effect on the non-U.S. company? Let’s assume the company acts pragmatically; it would only move away from using the U.S. dollar if it is better off by doing so. The discussion around this question usually tends to focus on the potential technological advantages of a CBDC and doesn’t grapple with the underlying reasons for the dominance of the dollar. That is, advocates for a CBDC tend to promote the potential for a CBDC to reduce payment frictions by lowering transaction costs, enabling faster settlement speeds, and providing a better user experience. I am highly skeptical that a CBDC on its own could sufficiently reduce the traditional payment frictions to prevent things like fraud, theft, money laundering, or the financing of terrorism.12 Though CBDC systems may be able to automate a number of processes that, in part, address these challenges, they are not unique in doing so. Meaningful efforts are under way at the international level to improve cross-border payments in many ways, with the vast majority of these improvements coming not from CBDCs but improvements to existing payment systems.13

For argument’s sake, though, let’s suppose that this foreign CBDC is more attractive for payments to the non-U.S. company, perhaps for technological reasons, or because the preferences of the firm’s consumers or trading partners change in response to the introduction of the CBDC. Due to the well-known network effects in payments, the more users the foreign CBDC acquires, the greater will be the pressure on the non-U.S. company to also use the foreign CBDC. In this case, it is true that the appeal of the foreign CBDC as a transactions medium—not as a unit account or store of value—might gain at the expense of the dollar. These effects will likely only be on the margin because they rely on a large enough number of individuals and businesses being nearly indifferent between the dollar and the foreign currency in CBDC form.

But the broader factors underpinning the dollar’s international role would not change. Changing those factors would require large geopolitical shifts separate from CBDC issuance, including greater availability of attractive safe assets and liquid financial markets in other jurisdictions that are at least on par with, if not better than, those that exist in the United States. The factors supporting the primacy of the dollar are not technological, but include the ample supply and liquid market for U.S. Treasury securities and other debt and the long-standing stability of the U.S. economy and political system.14 No other country is fully comparable with the United States on those fronts, and a CBDC would not change that.

Finally, as I’ve noted before, it is possible that a foreign-issued CBDC could have the opposite of its intended effect and make companies even less willing to use that country’s currency. Since digital currencies would make it easier for a government to monitor transactions, shifting to a CBDC might make a company less willing to use that country’s currency. For example, I suspect that many companies will remain wary of China’s CBDC for just this reason.

U.S. CBDC

I am also skeptical that a U.S. CBDC would affect this hypothetical foreign company’s decisionmaking. A U.S. CBDC is unlikely to dramatically reshape the liquidity or depth of U.S. capital markets. It is unlikely to affect the openness of the U.S. economy, reconfigure trust in U.S. institutions, or deepen America’s commitment to the rule of law. As I have said before, the introduction of a U.S. CBDC would come with a number of costs and risks, including cyber risk and the threat of disintermediating commercial banks, both of which could harm, rather than help, the U.S. dollar’s standing internationally. Like a foreign CBDC, the technological advantages of a U.S. CBDC would have a hard time overcoming long-standing payments frictions without violating international financial integrity standards. For the non-U.S. company already conducting its business in dollars, introducing a U.S. CBDC would not provide material benefits over and above the current reasons for making U.S. dollar-denominated payments. For non-U.S. companies conducting their business in currencies other than dollars, a U.S. CBDC similarly would likely not be preferred to their current options. It could be that individuals outside the United States would find a U.S. CBDC particularly attractive, but, again, making a U.S. CBDC globally available would raise a number of issues, including money laundering and international financial stability concerns. And as with a foreign-issued CBDC, the dollar’s function as a unit of account and store of value is unlikely to be affected, resulting in a limited effect on the international role of the dollar.

Stablecoins

The last scenario I want to consider is one in which a privately issued stablecoin pegged to a sovereign currency is available for international payments. Stablecoins are crypto-assets that aim to maintain a stable value relative to a specified asset or pool of assets.15 The reasons that stablecoins may be more attractive than existing options for payments include their ability to provide real-time payments at lower cost between countries that were previously poorly serviced and to provide a safe store of value for individuals residing in or transacting with countries with weak economic fundamentals. This is different than an intermediated U.S. CBDC, for which access in developing economies would depend on banks’ incentives to provide such access. Stablecoins, however, may be held directly in any country that allows its citizens to do so. To improve payments, especially for jurisdictions that are not well served under the current global payments ecosystem, stablecoins must be risk-managed and subject to a robust supervisory and regulatory framework.

Could such an asset affect the role of the U.S. dollar? Once again, I am unsure whether even a large issuance of a stablecoin could have anything more than a marginal effect. It has often been suggested by commentators that private money-like instruments such as stablecoins threaten the effectiveness of monetary policy. I don’t believe that to be the case, and it should be noted that nearly all the major stablecoins to date are denominated in dollars, and therefore U.S. monetary policy should affect the decision to hold stablecoins similar to the decision to hold currency. This follows from a vast body of evidence in international economics showing how countries pegging their exchange rates effectively import monetary policy from the country to which their currency is pegged.16

Also, because stablecoins are pegged to the dollar, they may increase rather than reduce the primacy of the dollar abroad, since demand for stablecoins increases demand for dollar-denominated reserve assets held by the stablecoin issuer.

Conclusion

The ongoing debate over the risks and benefits of a CBDC is important, and I am happy to continue to engage with both advocates and skeptics of CBDCs. But, for the reasons I have laid out, I don’t think there are implications here for the role of the United States in the global economy and financial system. We should instead focus and debate the salient CBDC-related topics, like its effects on financial stability, payment system improvements, and financial inclusion. Thank you again for having me to participate in this fantastic event.

1. These views are my own and do not represent any position of the Board of Governors or other Federal Reserve policymakers. Return to text

2. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2022), “Money and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation” (PDF) (Washington: Board of Governors, January). Return to text

3. See Christopher J. Waller (2021), “CBDC: A Solution in Search of a Problem?” speech delivered at the American Enterprise Institute, Washington (via webcast), August 5. Return to text

4. See Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2013), “Federal Reserve History: Creation of the Bretton Woods System,”webpage. Return to text

5. See Committee on the Global Financial System (2020), “U.S. Dollar Funding: An International Perspective,” (PDF) CGFS Papers 65 (Basel, Switzerland: CGFS, June). Return to text

6. These figures are taken from Carol Bertaut, Bastian von Beschwitz, and Stephanie Curcuru (2021), “The International Role of the U.S. Dollar,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Oct. 6). Return to text

7. See Ethan Ilzetzki, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff (2019), “Exchange Arrangements Entering the Twenty-First Century: Which Anchor Will Hold?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 134 (May), pp. 599-646. Return to text

8. See Bertaut, von Beschwitz, and Curcuru “International Role of the U.S. Dollar,” in note 6; and Emine Boz, Camila Casas, Georgios, Georgiadis, Gita Gopinath, Helena Le Mezo, Arnaud Mehl, and Tra Nguyen (2020), “Patterns in Invoicing Currency in Global Trade” IMF Working Paper WP/20/126 (Washington: International Monetary Fund, July). Return to text

9. For example, pass-throughs of exchange rate changes to U.S. inflation are reduced materially when the overwhelming majority of U.S. imports are invoiced in U.S. dollars. Return to text

10. See Board of Governors, “Money and Payments,” p. 15, in note 2. Return to text

11. See Committee on the Global Financial System, “U.S. Dollar Funding,” in note 5. Return to text

12. The legal and reputational risks associated with noncompliance with requirements on anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism often result in financial institutions choosing to be very cautious, including by requiring manual intervention in cases of uncertainty, which decreases speed and increases costs of cross-border payments. See Financial Action Task Force (2021), Cross Border Payments: Survey Results on Implementation of the FATF Standards (PDF) (Paris: FATF, October). Return to text

13. See Financial Stability Board (2020), Enhancing Cross-border Payments: Stage 3 Roadmap (PDF) (Basel, Switzerland: FSB, October). Return to text

14. Several recent studies set forth similar perspectives, including the following: U.S. Department of the Treasury (2022), The Future of Money and Payments: Report Pursuant to Section 4(b) of Executive Order 14067 (PDF) (Washington: Department of the Treasury, September); and Bertaut, von Beschwitz, and Curcuru, “International Role of the U.S. Dollar,” in note 6. Return to text

15. See Christopher J. Waller (2021), “Reflections on Stablecoins and Payments Innovations,” speech delivered at “Planning for Surprises, Learning from Crises,” 2021 Financial Stability Conference, Cleveland (via webcast). Return to text

16. See, for instance, Maurice Obstfeld and Alan M. Taylor (2004), Global Capital Markets: Integration, Crisis, and Growth(New York: Cambridge University Press). Return to text

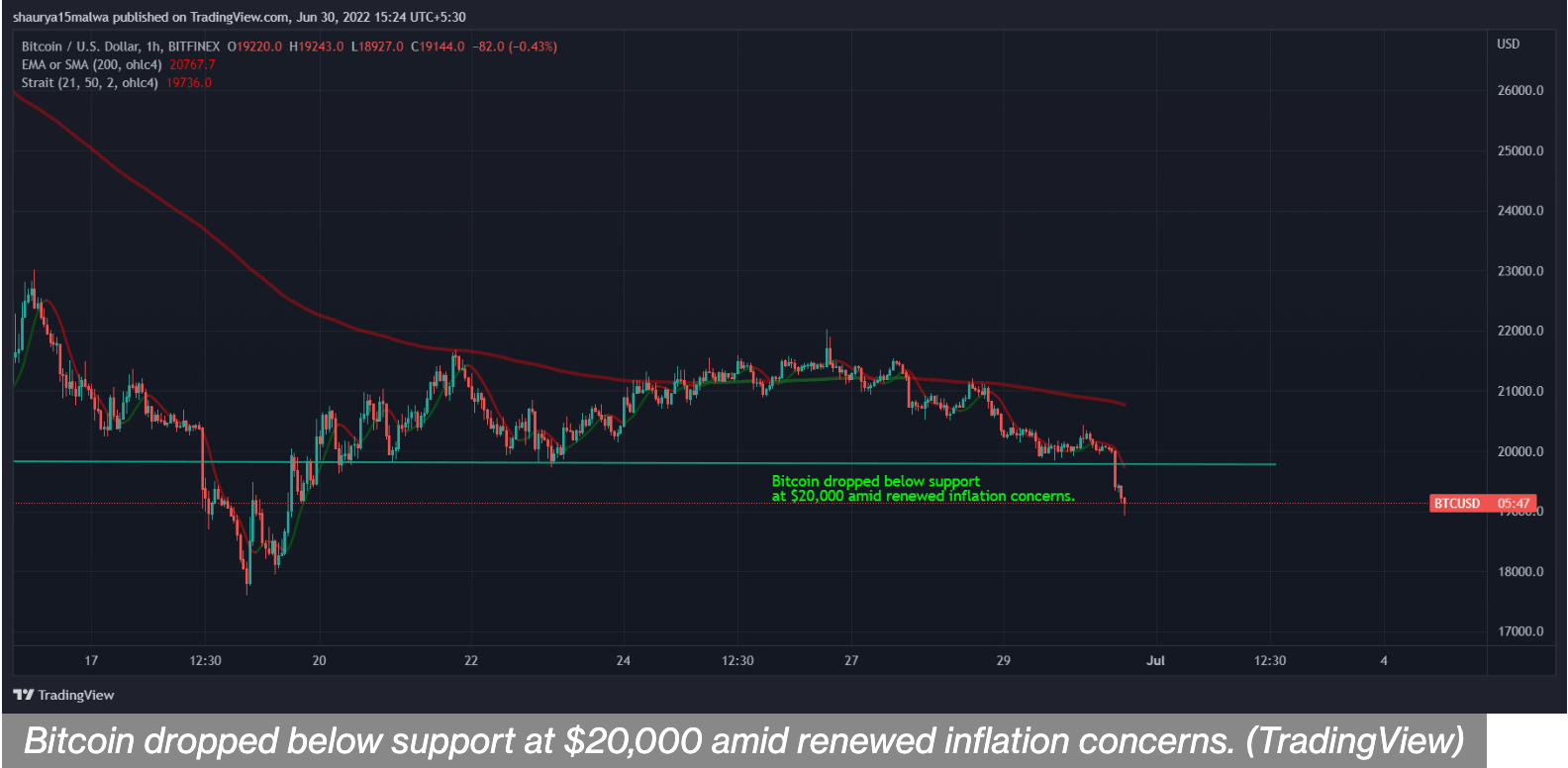

Jun 30, 2022 — Central bank leaders warned Wednesday that inflation is going to last longer than some estimated.

Bitcoin fell toward $19,000 during Asian afternoon hours after central bankers renewed inflation warnings at the European Central Bank’s annual forum on Wednesday.

The asset dropped 5.5% in the past 24 hours, and is on track for a record 40% monthly decline. Other large cryptocurrencies also weakened, with ether dropping 9.9% in the past 24 hours and Solana’s SOL falling as much as 11%. Total cryptocurrency market capitalization fell 4.3%.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell reiterated the central bank’s commitment to increasing interest rates to curtail inflation. Speaking at the ECB meeting, he said he was more concerned about the challenge posed by inflation than about the possibility of higher interest rates pushing the U.S. economy into a recession.

“Is there a risk we would go too far? Certainly, there’s a risk,” Powell said. “The bigger mistake to make – let’s put it that way – would be to fail to restore price stability.”

Powell said the Fed had to raise rates rapidly, Reuters reported, adding that a gradual increase could cause consumers to feel that higher prices of commodities would persist. About a week ago, his comments suggested rate hikes could soften before next year.

U.S. equity market futures fell following Powell’s comments, with S&P 500 futures dropping 1.59% and those on the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 falling 1.9%. Asian markets were in the red with Japan’s Nikkei 225 declining 1.54% and the Asian-focused index Asia Dow falling 1.14%.

Central banks across the globe are weighing interest rate increases amid surging price pressures. Spain reported a 37-year record inflation of 10% earlier this week, while India and China are grappling with the risks of economic contraction.

Such concerns add to already critical selling pressure on bitcoin. The crypto has traded similarly to risky technology stocks in the past few months and has fallen 58% this year.

Contagion risks from within the crypto industry, such as the possible insolvency of crypto lenders and the blowup of prominent crypto fund Three Arrows Capital, have further caused downward pressure on the asset that was otherwise conceived as a potential hedge against inflation.

Michel Euler/Pool via REUTERS

June 1 – Jamie Dimon, Chairman and Chief Executive of JPMorgan Chase & Co described the challenges facing the U.S. economy akin to an “hurricane” down the road and urged the Federal Reserve to take forceful measures to avoid tipping the world’s biggest economy into a recession.

Dimon’s comments come a day after President Joe Biden met with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell to discuss inflation, which is hovering at 40-year highs.

“It’s a hurricane,” Dimon told a banking conference, adding that the current situation is unprecedented. “Right now, it’s kind of sunny, things are doing fine. Everyone thinks the Fed can handle this. That hurricane is right out there down the road coming our way. We just don’t know if it’s a minor one or Superstorm Sandy,” he added.

The Fed is under pressure to decisively make a dent in an inflation rate that is running at more than three times its 2% goal and has caused a jump in the cost of living for Americans. It faces a difficult task in dampening demand enough to curb inflation while not causing a recession.

“The Fed has to meet this now with raising rates and QT (quantitative tightening). In my view, they have to do QT. They do not have a choice because there’s so much liquidity in the system,” Dimon said.

Major central banks, already plotting interest rate hikes in a fight against inflation, are also preparing a common pullback from key financial markets in a first-ever round of global quantitative tightening expected to restrict credit and add stress to an already-slowing world economy.

The inflation battle has become the focal point of Biden’s June agenda amidst his sagging opinion polls and before November’s congressional election.

Uncertainty about the U.S. central bank’s policy move, the war in Ukraine, prolonged supply-chain snarls due to COVID-19 and higher Treasury yields have rocked global stock markets, with the benchmark S&P 500 index (.SPX) falling 13.3% year-to-date.

“You gotta brace yourself. JPMorgan is bracing ourselves, and we’re going to be very conservative in our balance sheet,” Dimon added.

SOFT LANDING?

Wells Fargo & Co’s (WFC.N) CEO warned that the Federal Reserve would find it “extremely difficult” to manage a soft landing of the economy as the central bank seeks to douse the inflation fire with interest rate hikes. The CEO of the fourth-largest U.S. lender also said that Wells Fargo is seeing a direct impact from inflation on consumers’ spending, particularly on fuel and food.

“The scenario of a soft landing is … extremely difficult to achieve in the environment that we’re in today,” Wells Fargo Chief Executive Officer Charlie Scharf said at the conference.

“If there is a short recession, that’s not all that deep… there will be some pain as you go through it, overall, everyone will be just fine coming out of it,” he added.

Scharf said while the overall consumer spending is strong, growth is slowing.

“Corporations are still spending, where they can they’re increasing inventories … we do expect the consumer and ultimately businesses to weaken, which is part of what the Fed is trying to engineer but hopefully in a constructive way,” he added.

Recent Fed reports and surveys reported households on average in a strong financial position, with working families doing well, and unemployment at levels more akin to the boom years of the 1950s and 1960s. Wages for many lower-skilled occupations are rising, and bank accounts, on average, are still flush with cash from coronavirus support programs.

But confidence has waned, and in a recent Reuters/Ipsos poll the economy topped respondents’ list of concerns.

“I don’t think our crystal ball relative to the macro later this year, 2023, 2024 is necessarily any better than others. Clearly, we’re going to see with the Fed actions different impacts in different businesses,” GE CEO Larry Culp, told the conference. Still, not everyone in corporate America is seeing slowdown.

“Of the vast majority of the markets we serve are still quite strong,” Caterpillar Inc CEO Jim Umplebly said.

“And our challenge at the moment, quite frankly, is supply chain, our ability to supply enough equipment to meet all the demand that’s out there,” he added.

The Fed’s Board of Governors released the May 2022 Financial Stability Report, which presents key insights into the state of the American economy. What did the Federal Reserve’s latest decisive document reveal?

The Fed’s Board of Governors released the May 2022 Financial Stability Report, which presents key insights into the state of the American economy. What did the Federal Reserve’s latest decisive document reveal?

Monday, May 9, the central bank of the United States shared its biannual report on the national financial system. While the report’s purpose is to assess the resilience of the U.S. economy, it also identifies and measures significant risks.

In the most recent edition, the Fed Financial Stability Report warns of “increased uncertainty about the economic outlook.”

Important takeaways from the Fed Financial Stability Report

As of May 2022, the Federal Reserve has identified a series of risks contributing to market liquidity decline:

- Increasing interest rates;

- Russian invasion of Ukraine;

- Omicron variant news;

- Elevated inflation;

- Monetary policy tightening;

- Employment losses;

- High debt levels in China

Dr. Lisa Cook Credit: Harley Seeley for Minneapolis Fed photo

The Senate confirmed economist Lisa Cook on Tuesday to serve on the Federal Reserve’s board of governors, making her the first Black woman to do so in the institution’s 108-year history.

Her approval was on a narrow, party-line vote of 51-50, with Vice President Kamala Harris casting the decisive vote.

Senate Republicans argued that she is unqualified for the position, saying she doesn’t have sufficient experience with interest rate policy. They also said her testimony before the Senate Banking Committee suggested she wasn’t sufficiently committed to fighting inflation, which is running at four-decade highs.

Cook has a doctorate in economics from the University of California, Berkeley, and has been a professor of economics and international relations at Michigan State since 2005. She was also a staff economist on the White House Council of Economic Advisers from 2011 to 2012 and was an adviser to President Biden’s transition team on the Fed and bank regulatory policy.

Some of her most well-known research has focused on the impact of lynchings and racial violence on African American innovation.

Cook is only the second of Biden’s five nominees for the Fed to win Senate confirmation. His Fed choices have faced an unusual level of partisan opposition, given the Fed’s history as an independent agency that seeks to remain above politics.

Some critics charge, however, that the Fed has contributed to the increased scrutiny by addressing a broader range of issues in recent years, such as the role of climate change on financial stability and racial disparities in employment.

Biden called on the Senate early Tuesday to approve his nominees as the Fed seeks to combat inflation.

“I will never interfere with the Fed,” Biden said. “The Fed should do its job and will do its job, I’m convinced.”

Fed Chair Jerome Powell is currently serving in a temporary capacity after his term ended in February. He was approved by the Senate Banking Committee by a nearly unanimous vote in March.

Fed governor Lael Brainard was confirmed two weeks ago for the Fed’s influential vice chair position by a 52-43 vote.

Philip Jefferson, a economics professor and dean at Davidson College in North Carolina, has also been nominated by Biden for a governor slot and was approved unanimously by the Finance Committee. He would be the fourth Black man to serve on the Fed’s board.

Biden has also nominated Michael Barr, a former Treasury Department official, to be Fed’s top banking regulator, after a previous choice, Sarah Bloom Raskin, faced opposition from West Virginia Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin.

Cook, Jefferson, and Barr would join Brainard as Democratic appointees to the Fed. Yet most economists expect the Fed will continue on its path of steep rate hikes this year.

Courtesy of NPR/Associated Press

Courtesy of Matthew Boesler and Steve Matthews, Bloomberg

-

Interest-rate increase marks largest upward move since 2000

-

Stocks rally as Powell pushes back on 75 basis-point Fed move

The Federal Reserve delivered the biggest interest-rate increase since 2000 and signaled it would keep hiking at that pace over the next couple of meetings, unleashing the most aggressive policy action in decades to combat soaring inflation.

The U.S. central bank’s policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee on Wednesday voted unanimously to increase the benchmark rate by a half percentage point. It will begin allowing its holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to decline in June at an initial combined monthly pace of $47.5 billion, stepping up over three months to $95 billion.

“Inflation is much too high and we understand the hardship it is causing and we are moving expeditiously to bring it back down,” Chair Jerome Powell said after the decision in his first in-person press conference since the pandemic began. He added that there was “a broad sense on the committee that additional 50 basis-point increases should be on the table for the next couple of meetings.”

Powell’s remarks ignited the strongest stock-market rallyon the day of a Fed meeting in a decade, as he dashed speculation that the Fed was weighing an even larger increase of 75 basis points in the months ahead, saying that it is “not something that the committee is actively considering.”